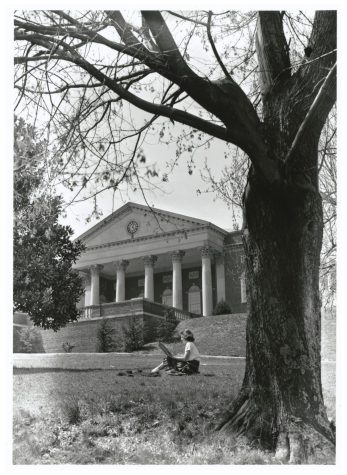

100 years of our auditorium

Photo provided by Will Bumgarner

Aerial view of the Reynolds Auditorium.

February 13, 2023

Atop Society Hill sits the crown jewel of a historical area: a campus dedicated to a man who formed the city below with a grand auditorium at center stage, marked with the legacy of his widowed wife. For a school defined by arts, excellence, and tradition throughout the last century, it seems only fitting it would possess such an impressive landmark.

The RJ Reynolds auditorium was a part of a conjoint effort between Katharine Reynolds, P.H. Hanes, and the city of Winston-Salem.

“That was a time in the U.S. where auditoriums of that nature were becoming fairly common in larger cities,” Arts Magnet Director Pamela Kirkland said. “Ours just happened to be a part of Katharine’s vision.”

Hanes proposed a donation to the city in which he would give forty-seven acres of land to be used solely for a park and possible school buildings. At the time, Mrs. Reynolds was beginning to make her own offers regarding the location of a school dedicated to her late husband. Upon hearing this, she presented an adjacent proposition in which she would purchase and donate an area known as “Silver Hill,” above the future P.H. Hanes Park. Mrs. Reynolds’ land would then be used for her auditorium and the city’s new school, our RJ Reynolds High School.

“When [Katharine’s] husband died, she was undoubtedly one of the richest people in North Carolina,” Alumni President Harry Corpening said. “She was even one of the richest women in America.”

Mrs. Reynolds and the Hanes brothers’ cooperation resulted in what was, at the time, the nation’s third-largest donation from individuals to a public school system. Only through their vast resources and influence was such a significant project made possible.

At the age of forty, Mrs. Reynolds remarried J. Edward Johnston in hopes of beginning a new life with him.

“She had a child—a daughter that lived less than 24 hours—with Mr. Johnston, and she wanted to have a family with him,” Corpening said. “And so they tried again. The second child lived; she didn’t.”

The school opened on January 15th, 1923, after a fire at Winston High School on Cherry Street forced them to house the newly displaced students. Classes were held in the twenty rooms that had been completed on the second floor of the main building. A few additional classes took place at St. Paul’s Church.

“So the celebration of the 100th Anniversary was started a little bit early,” Kirkland said. “January through May was the first semester, but it was not yet considered RJ Reynolds High School.”

Mrs. Reynolds had grand visions regarding her new auditorium’s future.

“Around that time, a lot of people in New York City would go to Florida to spend some time and then come back,” Corpening said. “Winston-Salem is about halfway between New York City and Florida. [Katharine] fully expected that once the auditorium was built that folks would come on train to Winston-Salem. You’d pull in, stay at a nice hotel if you wanted to… you would eat at a nice restaurant… then folks would get on the electric streetcars and take them to the auditorium. They would walk up the hill, see a play, then go back, spend the night in the hotel, get on the train the next day and go to Florida. Then do the same thing coming back. So the auditorium was meant to be a real economic engine for the community.”

Mrs. Reynolds also hoped their new school would be like no other in the nation. In many regards, it had already done so, fully equipped with electricity and air conditioning forty years before the average home would possess it.

“She planned on having the largest art museum in North Carolina at the school,” Corpening said. “And I’m sure she expected to have the best teachers money could buy.”

Her plan included not only that but the addition of an identical main building on the opposite side of the auditorium with columned walkways tying them all together.

“I’m sure she fully expected to live a long time and would endow such things, but she didn’t,” Corpening said. “So, these great plans she had never came to fruition. When she died, those ideas died.”

In her absence, Mrs. Reynolds left the auditorium with four goals for its future: “to showcase accomplishments of public school students, civic or memorial occasions, religious programs, and musical and cultural programs featuring renowned artists.”

“I think it definitely did what Katharine would have wanted it to do,” Kirkland said. “There’s an element of inclusivity that we have now that we really try to be mindful of making that space available to the entirety of our community and having it be something that gives opportunities for all of our families and all of our students.”

Over the past century, it has not only highlighted local talent, but a variety of big names such as Harry Houdini, REM, Yo-Yo Ma, American Ballet Theatre, National Symphony Orchestra, Jim Croce, Indigo Girls, Doc Severson, Amy Grant, Ricky Scaggs, New York City Opera, and Vienna Boys Choir, to name just a few among the thousands of notable performances.

“Parkland and East and all the other high schools have what I would call gymnatoriums,” Corpening said. “They’re small auditoriums, they’re not bad, but they’re no Richard J. Reynolds Memorial Auditorium. We were lucky enough to host the Symphony and Yo-Yo Ma. Does anyone think he’s going to come play at Parkland or at East or Mount Tabor? That’s not knocking them. But you need a big enough place for him to come, a place that matches his magnitude.”

As we look towards its future, we must keep close to heart Katharine’s vision for the sacred space, stated upon a plaque of dedication within its grand lobby: “This auditorium is to be devoted to the cultivation of the arts and sciences, and to the education of people, in affectionate recognition of the life and services of him in whose honor and memory it is dedicated.”