Reflecting on a time of division and adversity

March 23, 2019

It is January 15, 1923 and students begin filing into the halls of RJ Reynolds High School for the first time, just six days after Winston High School burnt beyond repair. Being well before the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling, every student was white. Segregation was the rule and R.J. Reynolds High School was not yet a place for “Excellent instruction for every student.”

Flash forward 33 years, it is 1956 and Reynolds is still an all white school. One student, Kathryn Dalton, now Kathryn Snavely, is a senior and has never been to school with a non-white student. It is two years after the Supreme Court rejected the Jim Crow mantra of “separate but equal,” yet schools in North Carolina had not begun the process of desegregation.

When asked whether she thought that it was strange that her school was all white, Snavely said, “I didn’t because that’s the way all the schools were. None of the schools were [integrated]. It wasn’t that we didn’t want to, it’s just that wasn’t the way it was.”

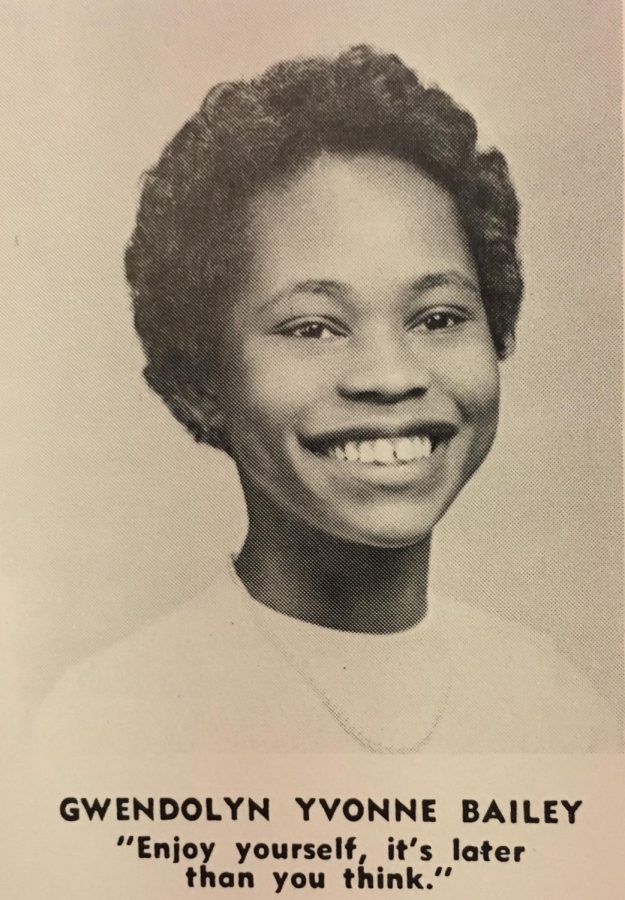

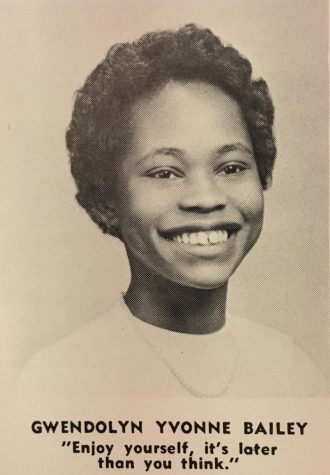

It did not stay that way for long. Just one year later, in 1957, select students across the state were chosen to be the first students to integrate high schools in North Carolina. Gwendolyn Bailey became the first African American student to ever attend Reynolds High School.

Other African American students in Greensboro and Charlotte had already begun classes and had received lots of hate. Reynolds Principal Claude Joyner was determined to prevent such things from happening at Reynolds.

The morning of Bailey’s first day things did not go as planned. Someone had painted racial slurs on the driveway by the auditorium and the assistant principal, John Tandy, could be seen running around campus trying to get it cleaned up.

Racial slurs were not Joyner’s only problem, crowds had gathered across the street on Hawthorne Road, hoping to catch a glimpse of Bailey. Fortunately, according to an article published in the Winston-Salem Journal in 1959, this had been planned for; Bailey was dropped off by her father on Northwest Boulevard and walked to school via the tunnel. Compared to the students in Greensboro and Charlotte, Bailey had a relatively calm day.

For the most part, schools stayed segregated because it was not required for students to attend certain schools and most chose to stay at their home school.

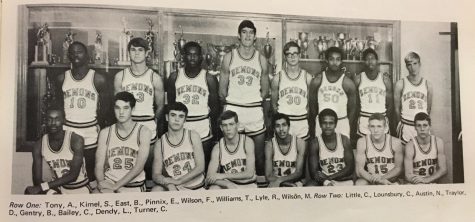

In 1966, Reynolds was still a predominately white school and across town, Atkins High School was a predominately black school. The two schools competed in separate athletic divisions because the North Carolina High School Athletic Association did not allow predominantly black schools to be members. That all changed in 1967 when the NCHSAA joined with the North Carolina High School Athletic Conference, the organization for primarily black schools. Two years later, Reynolds lost to Atkins in the semifinals of the state basketball championship. In a time of high racial tension the Reynolds players were not thinking about race; they just wanted to play.

Howard Hurt was the coach of the 1969 basketball team at Reynolds. He didn’t believe that any racial issues extended onto the court, the players just viewed Atkins as if they were any other rival.

“To be honest, we didn’t pay too much attention to it [race],” Hurt told the Winston-Salem Journal in March. “They’re there. They’re good. And we know they’re good, but I don’t think we made race a thing at all.”

Due to a court ruling that required the busing of students to schools across town, the schools of North Carolina were officially deemed desegregated in 1971. This resulted in some tension in the classroom and on sports teams; just four years later, the Reynolds’ boys basketball team won the state championship.

Athletics can be credited as one of the driving forces that brought students together. They were forced to attend the same school and sit in the same classrooms, but in order to be successful on the court they had to work together.

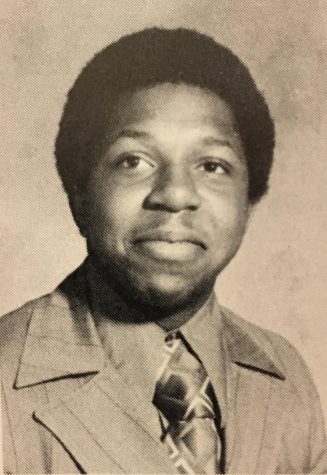

Rick Duckett was a student at Reynolds in 1975. He played JV baseball at Reynolds and recognizes the effect sports had on students.

“You have a segment that certainly will come together at a quicker pace because you have to pull together for a common goal,” Duckett said.

Duckett credits other activities as facets that brought students together as well as sports.

“There are many students who did not participate in sports that had to come together for various other reasons, whether it was for being in the band, whether it was chorus, whether it was some other aspect of extracurricular activities,” he continued.

Duckett was 15 when the school system began integration. He remembers lots of negative attention in the media around integration but does not remember it being that way for the students.

“Quite frankly, in the schools there was never the problem that supposedly was going to exist by integrating the schools,” Duckett said. “It was not an issue for the students as much as it was for… some parents [who] obviously had problems with it but that was their own issue…Once you got in the school, it really wasn’t that big of a deal, it really wasn’t.”

For some, like Gwendolyn Bailey, it was more a big deal. According to an article published in Winston-Salem Journal about Bailey’s graduation, she often said: “if only there had been another one.”

Bailey attended Reynolds for 21 months, she was the only African American student and spent much of her time feeling lonely. She had to miss her senior picnic because the location did not allow African American patrons. She was, however, able to attend the most important aspect of her senior year, her graduation. In 1959, Gwendolyn Bailey became the first African American student to graduate from Reynolds.

Since 1923, Reynolds has been a welcoming place to those that needed a place to learn. When Winston High School was ravaged by fire, Reynolds was opened prematurely to house the students so they could finish the school year. However, the sad reality is that at our school’s beginning, many students were not able to experience all that Reynolds had to offer because of the color of their skin.

Now, Reynolds has a mixture of students from different backgrounds, cultures and religions, a stark contrast from the entirely white population it originated with. Students come from all over the county to participate in our award winning arts programs. It truly is a place of excellent instruction in every class, every day, for every student.

Photos courtesy of Black and Gold